Webinar March 4th - Finding Songs On the Air: Lessons From Bretagne, France - University of New Mexico

The University of New Mexico College of Fine Arts is hosting me for their musicology colloquium series, Spring 2021 - “Ethnography and Creative Process in The Arts”. I am honored to be presenting through a webinar, open to all. March 4th, 2-3:30pm mountain time.

In this talk, I share how learning a Breton song opened me to the ways traditional music can transmit during the digital age. Participants will examine the songs they carry. We’ll be thinking about how regional culture transforms through digital interfaces.

Please register for “Finding Songs on The Air: Lessons From Bretagne, France” here.

Black Lives Matter, End of Tourism, Σούγια, Crete Magic, Imperialist Nostalgia, Carey Get Out Your Cane, Peasant Authenticity, Praise for Marthe Vassallo, Vacation Music, Cabbage

"Now I'm nostalgic for the future, which was my native land."

-Hari Kunzru, White Tears

Melanie at City of The Sun, Occupied Cohokia Territory , 2014 - photo by Mackenzie Stewart

Here is my summer newsletter. The voices of Black, Brown, Indigenous, & People of Color must be celebrated, uplifted, listened to, and passed on. Not 'now more than ever', but always, and consistently. The first part of the letter will focus on voices I have heard and want to pass on to you. I don't know if I'm doing anti-racist work right, or well, especially in the context of this newsletter. But to be silent for fear of making mistakes doesn't make any sense. If you're seeing a way I can do better, you can let me know. I hope we can all be in a continual state of learning, communicating, and acting for racial and social justice. Thanks :)

The second part of this letter was going to be an address of the most pressing questions of our time. If you are me. Such as: Am I, the young writer taking refuge in a remote village in Crete, witnessing the end of tourism? What does it mean when tradition, in this case Breton Fest Noz Dance/Musical culture and Salish txwəlšucid Language, get passed on in digital space? How do languages of English and French have colonial/capitalist concepts written into them, and how can this violence be rectified? When will America be worthy of its founding ideals? Can white people admit failure, and actualize healing by articulating our white supremacy?

But I only got to the Crete/Tourism inquiry. Otherwise this letter would have been way too long. But… Melanie… this newsletter IS way too long. Like, the entirety of it won't even fit in the email and I have to click a link at the bottom to see the whole thing! Touché.

The third part of this letter is some writing about Bretagne. It’s a story about a cabbage and a Queen with whom I intermingled in winter.

Disclaimer: There are going to be typos in this newsletter.

Without further ago, let’s get this party commenced. (that’s a direct quote from TV show Dickinson)

PART ONE

Je ne peux plus respirer / I can’t breathe

George Floyd wheatpaste in Brest, France

Here is a potential map of an anti-racism practice based on my own.

Begin by considering the symbolic action of breath in the movement for Black Lives with this podcast featuring Jungian analyst Fannie Brewster. Accompany this with M. NourbeSe Philip’s book Zong. It’s a literary object expressing wordlessness, loss of language, lack of breathe, drowning, and the voices of slaves murdered during the Middle Passage, stilling echo from the Atlantic Ocean in fragments of legalese.

Continue by imagining America begins the moment enslaved people arrive on its shores, in the podcast by Nikole Hannah Jones called 1619. Interrogate the trajectory of Black Life in America. The film Daughters of the Dust, the first person accounts of the Slave Narratives , Colson Whitehead’s novel The Underground Railroad, this documentary from 1968 about the heritage of slavery following Emancipation, the film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, this documentary about the life of a young woman in the Watts Section of Los Angeles in the 60s, this industrial film from Budweiser in the 70s which outlines a strategy for marketing malt liquor to Black communities, the Black Panthers documentary by Varda, Martin Luther King’s Beyond Vietnam speech: A Time to Break Silence, Audre Lorde’s 1978 essay Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power. Fill in the past centuries of American history with what you never learned in school. Learn that the past stays with us re: Jesamyn Ward’s novel Sing Unburied Sing. Know that the above is a non-exhaustive list, but a representation of one white person’s incomplete learning.

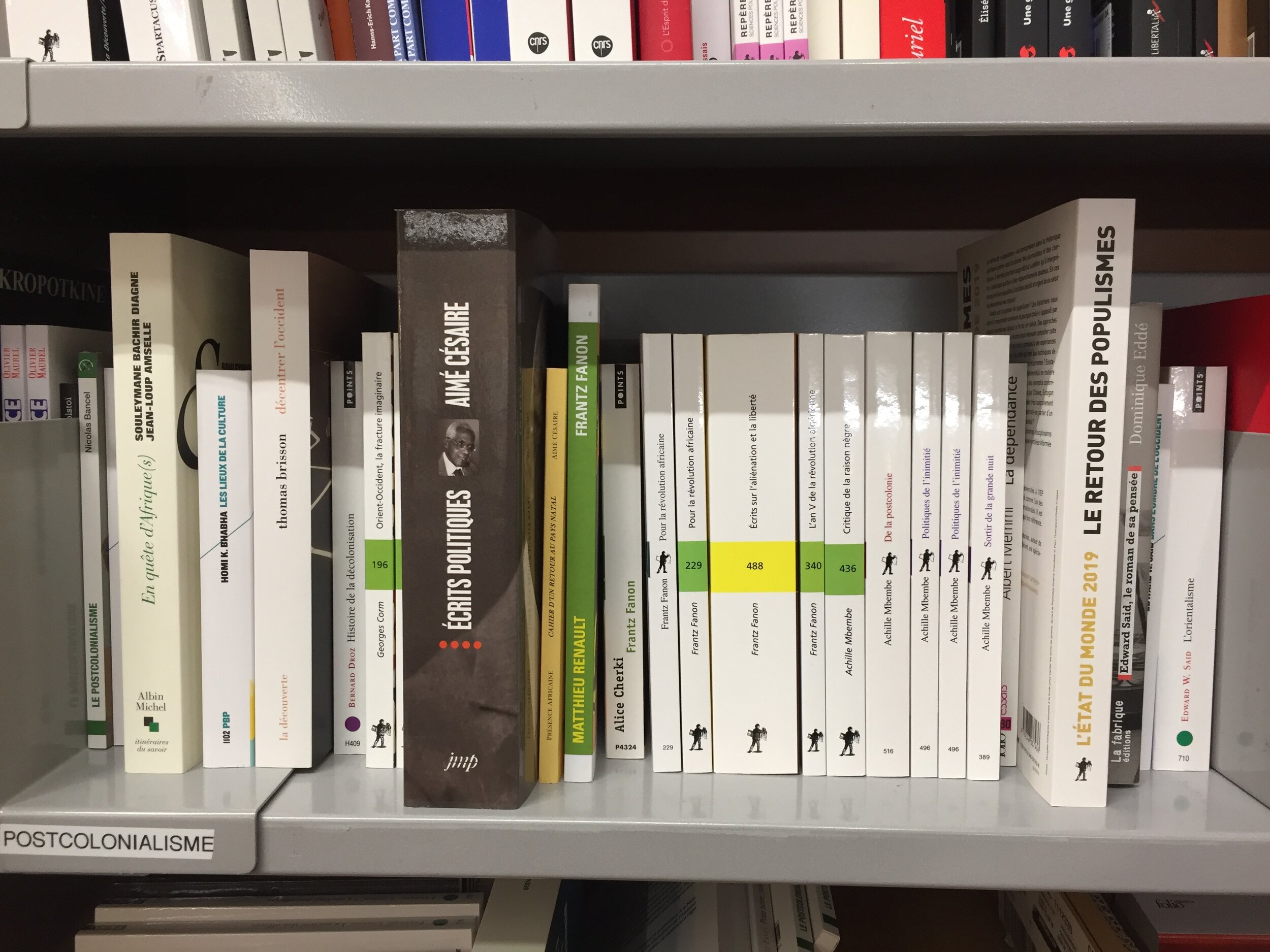

Dialogues Bookstore in Brest June 2020 - this major display of books about American racism

vs. selection about French colonialism same store same day.

Turn to music. Listen to this podcast by Wesley Morris about how white appropriation of Black expression is the basis of American popular music. Learn this again and again. Listen when banjoist Rhiannon Giddens says anything (What Folk Music Means...) I have a big vacancy in my mind regarding Black culture and experience throughout the 80s, 90s, 2000s and now. I try to bring nuance to my understanding of this time. I’ve started with a book of poetry called I’m so Fine: A List of Famous Men and What I Had On by Kadijah Queen. Or American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin by Terrance Hayes. With Cheryl Dunte’s film The Watermelon Woman. With Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah's story collection Friday Black. With Barry Jenkin’s Moonlight. Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric. Childish Gambino/Donald Glover’s This is America music video. Donald Glover’s TV show Atlanta. The film Get Out. This Vince Staples music video for Señorita wherein white people are entertained by the pain of People of Color from the protection of their/our own white privilege. I start to decompose my own. To do so, I must stay centered, pull together the energy for the long-haul, and create an anti-racist practice at a pace which is sustainable.

For this, I heed the following words of composer/producer King James Britt (twitter @kingbritt):

To all my black & brown family & our true allies, I wanted to express a few ways of centering yourself in this revolution that we are in.

One - Find a spiritual center. Whatever that may be for you, an altar, church, ritual, but something where you can tune into divine spirit. If we aren’t spiritually centered, we can’t find balance in the fight. It’s also a powerful revolutionary act. You are in full control of.

Two - detach from all of the noise. Social media has been a great tool for exposing the atrocities that are happening to our humanity and culture. But there is so much noise in these feeds which become distractions. Find your 3 favorite information sources and focus on that. Also a few friends you trust as information curators.

Three - do things you love. We can get swept up in the constant fight and forget our joy. Joy is one of the most powerful weapons because it creates contagious vibrations of loving feelings. It also helps keep your spiritual equilibrium.

Four - do what you feel you can do to help in the revolution. Don’t get guilt tripped into feeling you aren’t contributing. Find whatever resonates and feels good to you, to contribute. It could be just calling your friends for support. All forms of contribution count. Only you know your capacity to contribute in a healthy manner.

Five - continue to be your true authentic self. This is why we are here in physical form and is a powerful statement. To continue to be authentic in the eye of the storm. We need to continue to envision positive realness in the midst of the violence.

Six - gain the knowledge, laws, statistical breakdowns of wherever you live, your rights, all of it. The more you know, the less it can used ‘against’ you.

Seven - use your intuition. This is probably the most important of all. This applies to every single action in your life. If you are centered, your intuition is your antenna for what moves you will make at what times. It could be as simple as not walking down a certain street because you sense danger. Trust your gut and don’t always listen to all the advice that is given.

Eight - music. The universal language and vibrational healing. If you create your daily soundtrack to steer your emotions, that is a radical act of self care. Be intentional about your sonic diet. You can shift not only your mood but others as well thru the vibrations you push into the world.

Nine - self defense. With all revolution, there will be violence. You may not be subjected to it but if you are, be prepared. Whatever that looks like for you

Ten - Thank you.

Okay, this is Melanie again. I’m going to keep giving my suggestions for things to read and think about. With this newsletter and any other information you’re coming into contact with, don’t forget to breathe. Take in as much as you can at a time. Ignore what I write completely if needed. What I glean from King James Britt’s words above are to take care of my mental health, my spiritual state, so as to stay strongest in times of struggle.

Recommencing.

Listen to Code Switch podcast episode Why Now, White People? Do not let this revolutionary moment be a trend. It has all the hallmarks of a trend. Find others to hold you accountable in the process of dismantling white supremacy. Hold them accountable too. (Code Switch also just released an episode on Karens)

Read Peggy Mcintosh's list of 50 examples of white privilege. Read them aloud and with family and friends. Purchase Layla F. Saad’s Me and White Supremacy workbook. Do it. Take a break from it. Start again. Encounter the extensive world of google documents available to all: Scaffolded anti-racism resource guide, resources for anti-racist parenting, policing alternative resources, and this Black Lives Matter master document. If the phrase Black Lives Matter makes you uncomfortable- ask why that could ever possibly be true. Why would that statement ever need to be qualified. Read this piece, written by fellow Fulbrighter Sterling de Sutter Summerville on what allies can do to help the Black community. Check out episodes of Wyatt Cenac's TV show Problem Areas.

Treat Racism Like Covid-19 Protest Sign Guy

Acknowledge the systemic nature of racism/colonialism, embedded in the foundations of America, and especially the American economy. Of France’s too. In the institution of law enforcement. Note the difference in the words systemic and systematic. Educate with the de-colonial philosopher Frantz Fanon. Or the episode of 1619 podcast The Economy That Slavery Built. And Ta-Nehesi Coates The Case for Reparations. Figure out how to invest your money and/or time in Black businesses and institutions. Here is an incredible directory of that information by city. Put your money in Black owned banks, eat at Black owned restaurants, buy from Black owned clothing businesses. If you're like me, you dream in beautiful, flowing, colorful clothing. Here is a Black owned resort wear company, and another, and another.

Donate to the organizations propelling the Black Lives Matter Movement. A couple are Black Lives Matter and The Black Visions Collective. Find many more here under the donate tab.

With this video from The Root, come to question the white capacity to digest (Rankine) Black pain, and death, and suffering. Especially in videos of police brutality and killing.

Let's Talk About Race - image by Chris Buck

Know that Blackness is not a monolith. Focus and uplift the beauty, creativity, joy, pleasure and multifaceted richness of Black life. Highlight Black virtuosity, excellence, brilliance, creativity as much if not much more than the narratives which cast Black people as only victims. Introduce Black power, art, and expression into your everyday consumption of media. Know that doing so is an act which subverts history in the most generative of ways. Imagine what it would have been to grow up in a world where few of the characters on TV, in books, in films, in toys looked like me.

Black Power Naps - Image by Avi Avion

Support Black artists, collectives, and projects. A few which come to mind are the Black Power Naps project. Is the artist Rachelle Brown (@reshell-brown) who creates the NUDE events in LA. Is the Cave Canem Poetry Project. Listen, listen, and dance to Zakia Sewell's weekly show Questing W/ Zakia on NTS radio which freaking rules. Appreciate the stand-up comedy of Duclé Sloan.

I remind myself that there is no arrival. The goal is not to be a perfect white person who knows all. That’s not even possible. So I embrace two practices. The capacity for apology, and my own perpetual student-dom. Alishia McCullough lays out this idea:

from Alishia McCullough's '7 Circles of Whiteness' post

This concludes what I have currently culled in a beginning, ever-evolving, anti-racist practice. I’ll now transition into the second part of the newsletter. My life as an artist, writer, musician, stranger, tourist, friend to many, are enabled by the infrastructure of whiteness, affording me things I have not earned.

Readers, please feel free to disregard the next parts of this letter. To give all of your attention to the work of the artists, thinkers, leaders, activists, and causes that are not emanating from me, a white writer musician vacationing in Crete.

PART TWO

The End of Tourism?

Tour Mat. Great for Tourists.

"Who knows the tradition? We do. We own that shit."

-Hari Kunzru, White Tears

I’m in the small village of Sougia (Σούγια) on the south coast in western Crete. At this point, I’ve moved out of where I was living in Brest, vacating to a small room here at the Lotos Seaside Hotel. Though a month-long vacation may seem extravagant, I assure you I am here on business. Someone has to write the ethnography of umbrella shading practices, tanning strategies, moisturization customs, wifi-finding traditions, and various techniques of consuming Cretan olive oil. In addition to these anthropological investigations, I am also researching my own relaxation threshold as I develop a habitus of swimming, piano playing in bar, and consistent vitamin D exposure.

Crete tourism is pretty new. Joni Mitchell is the prototype of Crete tourist. In 1971, she lived in a cave in Matala, not far from this town. During her dulcimer accompanied sojourn, Joni wrote songs that would become the album Blue. On this album, one finds the song Carey, which describes in detail her lifestyle in Matala. The song is a gem of musical ethnography. Joni is my spirit guide right meow. I’m writing songs on the banjo and at the piano in the lotos bar (I guess it’s not capitalized). Originally I wrote it off as a place where retired men go to day drink. But now I’m observing a diverse clientele. It’s like the town’s rec room, and the town is made-up of all the people you might find at a neighborhood block party. The customers cannot be typecast.

I was told by the waiter, who is also an energy healer (He says spraining my left ankle means I have female problems and a lack of self confidence. Great.) that earlier this summer a group of 10 or 20 friends lived at this table for a week. Yes, this table where I write you from. They slept on the bench seats, charged their phones with that lime green power strip, and lived beside this pile of backgammon boards. Other people in Sougia stay in tents and semi-permanent campsites by the cliffs. It’s not unlike Matala in 1971. Except there’s a lot more electronic music coming from bluetooth speakers.

I watched this Crete British travel video from the 60s. We can see here the creation of Crete’s ‘peasant authenticity’ as a consumable tourist thing. I’ve been having a weird nostalgia about a tourism era I never experienced. I guess others are too. Evidenced by this playlist, and this one too. I’ve noticed cool honky tonk buddies displaying appreciation, in a totally non-ironic way, for the early work of Jimmy Buffet. Vacation music. What’s up with it? It articulates a fantasy of place and much as it does a remove from being anywhere real.

The tourist comes as consumer of 1. The vacation experience which supersedes any complications the place may put up against a smooth experience of pleasure and relaxation. And 2. The authenticity experience wherein the tourist encounters the messy stuff that makes the place special. Even if that stuff is performed as spectacle or simulacra.

Reassuring message from a knife store in Chanià. Crete is known for its tradition of knife crafting.

We went on a little jaunt in Bretagne to beautiful tourist trap Post Aven. This year the music and dance events that make Bretagne famous in France for being a place with an authentic culture, are cancelled. The Cercle Celtique groups who dress in traditional Breton costume and perform the dances and songs are on 2020 hiatus. The Festoú Noz and Deiz I was attending in Bretagne went on live stream. This deserves a post/chapter/exposé of its own.

Fest Noz de Confinement on Facebook Live.

Cute Tourist Trap Pont Aven... How do you wear a mask at a restaurant?

Authentic Breton-ness in Pont Aven is limited to what can be purchased in the shops. This includes striped shirts, Breton cookies, crepes crepes and more crepes, cider, raincoats, and butter. I spent a lot of time looking at a rack of greeting cards which cast the Breton people as backwards, old-fashioned, janky people. In the cards, rotund women in full traditional Breton wear including decorative coifs navigate a cartoon world of tractors, crass sexual innuendo, barn animals, and remove from modern technology. It’s like Bretons are to France what Hillbillies are to America. Also maybe what indigenous people are to America. What does the tourist to Bretagne want to experience? What do they get instead? We got an experience of an abandoned go-kart rink.

Abandoned Go-Kart Rink near Pont Aven Bretagne

Photographing the Breton Flag in Go-Kart Rink - image by duskin drum

In any case, the regional expressions of a place are smoothed over and made less powerful because of mass tourism to the region. The tourists, in seeking to experience “the real thing” are complicit in its erasure. A tourist returns a decade later to find the quaint eccentricities they loved there are no longer there. This leads to a bad case of what anthropologist Renato Rosaldo calls ‘Imperialist Nostalgia’. A new friend, honky tonk singer and anthropologist Kristina Jacobsen tipped me off to this concept. She’s doing cool work in Sardegna, collaborating with traditional singers and players there. The Sards too have had to protect their language and traditions from same-making effects of mass tourism. Blink and the complex-awe-inducing-terrain-of-mystery-and-meaning-you-know-as-home will become just another Italian island with good photo opportunities.

case n' point. Chanià Old Town.

Vasso at the bakery here in Sougia estimates that tourism is down by 50% this year. Michele at the Cafe Santa Irene tells me that if people don’t start showing up, some of the business owners are going to… [pantomimes gun to head]. Crete has had thousands of years of shifting rulership. There have been many seasons of vibe here. Scholar and boyfriend duskin calls what we are living in the Season of Petroleum. I believe that contained within the Season of Petroleum is the Month of Mass Tourism. That month is probably also July, and we are probably also at the end of it. Sorry about this newsletter being a month late. Happy summer solstice.

The corona confinement moment represents a clear rupture in the Month of Mass Tourism. The ease of movement afforded by cheap fuel for planes, trains, and automobiles is a thing of the past. The dream of making seamless transitions between metropoles, rural enclaves, and scenic locales is one we collectively are waking from.

Crete is refreshingly messy. France is formulaic as fuck. America is chaos. My expatriated uncle told me in all seriousness to apply for asylum. Around here I say I’m from France first. Originally from the United States- I say that as a follow up. “It’s a war zone over there,” a stranger said to me the other day.

Stefanos at the grocery store tells me to move to Sougia. What would I do all day? That’s the thing though, about a small place. It becomes more intricate the longer it is witnessed. Tourism tells us a place is its surface. Through a combination of AirSpace and Millennial Premium Mediocrity, we are supposed to slide in and slide out of travel experiences unscathed, and with formulaic documentation of the experience for social media.

I cracked up the other day watching two teenage female appearing people get their younger brother appearing person to take “hot bikini beach photos”TM for them. Returning the favor, the young women took a video of the brother dabbing. I think for TikTok. I note that the process of procuring content is never equivalent to what that content conveys as is happening. More likely getting the content involved the coercion of siblings/girlfriends/grandparents/friends/strangers into photo taking.

A menu in Sougia

I was at the Anchorage restaurant last night paying close attention to the songs playing. I asked the waitstaff about them.

This is a revolutionary song, says Costas. For what revolution? I ask. There was never a revolution in Greece. He says. The songs are like a stockpile for when the real thing happens.

Then a song about labor.

Then a song by a woman whose voice sounds like a man.

Is this Rebetiko music? Yes.

But this one is a Cretan song from a place close by here, in the mountains I drove through to get to Sougia. There were two families, Jason says, and a vendetta between them. The song talks about the arrival of a cool, clear February morning. On this morning one family will attack the other family. Leaving “children without mothers, wives without husbands”. Hundreds were killed in this feud over the generations. Over what? I ask. The same usual thing. Someone stole someone else’s sheep. Then it just escalated? Yep.

Jason has a friend from one of the families who is best friends with a guy from the other.

Surely they know the history?

Yeah but they don’t care. It’s over now and no one cares.

Another guy at the table is camping down the beach. Do you work here? I ask. No, I’m a client. He says. The client/camper is happy because it’s not too busy in Sougia this year. He can camp longer. But sometimes, there is a bit of trouble with the police. It’s illegal, the camping? I ask. What, it’s legal in your country? No. It’s not the town that gives a shit, he says, but police who come in once in a while and make people move who are too near the riverbed.

The riverbed is dry. I put my hand to it on the new moon and feel the moisture below the sand. The shadows of two cats pass by. There are the outlines of cement infrastructural implements on the banks. Around here somewhere are Roman ruins. I’ve only strolled down here at night. Each time I’ve gotten a feeling to turn around.

This place does not feel dangerous though, overall. Already I know the names of enough people that if I was in danger in any place, I could call out to one or two of them.

The shipment truck pulls in front of the bakery. Mythos beers, Amstel light, kegs, Coca Cola, and six packs of liters of Samaria bottled water. So many bottles.

My first night, I go to the Santa Irene Cafe and I ask if its okay to drink from the tap. Michele, bar owner, says, yes, of course, he’s been drinking it his whole life, now he’s 57. Sure, he drinks the bottled water now, but only because it’s around. You know what’s in the bottled water? Formaldehyde he says. The same thing they put in a corpse.

The water is dead. He says this not about the bottled water but about the ocean, the Libyan Sea which once provided the commerce this place operated on. When I am at the Mediterranean, the consciousness of refugees crossing the water, sometimes drowning and sometimes arriving, is always with me. The disparity between my pleasure and the fact of this horror, this humanitarian crisis, is with me. I don’t know what to say about it more than this. I imagine these people every time I swim.

High tourist season 2020, Sougia, Crete

When the first campers came here fifty years ago, says the client/camper, this place was nothing. It was a place where two families fished and brought the animals down to (The feuding families???). All there was on the beach was a little dock and storage facility. The first tourists were full on camping hippies. (Joni? Is that you???)

The tap water is calcium rich. If you drink it, you will become a statue from within, says another man in the bar. By contrast, raki liquor is referred to as “Covid-Killer” by Costas.

The virus has not come to Crete, but as tourism returns this summer, there will be cases. All the locals I talk to know and accept this. I was swabbed on the tongue in the Heraklion airport. A gust of wind blew the paperwork corresponding with the test tubes onto the floor. I went to help pick them up and passed them back to the man in the hazmat suit, maybe in the wrong order. Outside of the airport, masks were in mild abundance. In Heraklion proper, there were even less. Now here in Sougia, they dangle from the ears of some waiters, bartenders, and vendors. No tourist or off-duty local wears one.

I wonder how much of the “casual, haphazard” narrative I am imposing on this place. Coming from France, the differences in social protocols are striking. The camper/client is unloading raki into a glass. He’s drinking it like water. Also next to him is a bottle of red wine he drinks from. Which do you prefer, I ask, wine or raki?

Raki, this isn’t raki, he says. The clear liquid he’s been drinking like water is water. He’s just put it in the plastic bottle that raki is sold in at the store. See, he says to me, that’s your preconception.

Welcome to Touristland! Old Town Chanià, Crete

A similar thing happened the other day. I was reading the Crete guide book, which described a traditional village day of celebration on the 20th of July. The people at the Santa Irene Cafe said there was a party on Saturday, the 19th, up on the hill above this town. There will be singing and dancing.

An image was conjured in my mind- the traditional summer festival in the rural outskirts of this ancient place. I asked some other people about the party. They affirmed it existed.

The night came and I missed it. A couple days later someone says, I thought we’d see you at the party- where were you? Oh, I got my days mixed up. Vacation, you know? How was it?

It was crazy. He goes on to talk about this event, which was actually the opening of the town’s nightclub for the season. Fortuna is the only nightclub in town. Maybe the tradition is buried in there, but more likely it was my own wishful thinking.

The garbage truck drives by during closing time at Anchorage restaurant. It’s just a regular pick-up truck like those smattered all around Jefferson County, Washington. Jason pops out of the restaurant with garbage bags in his hands, at the ready. This is a synchronized moment. Precipitated by what? He and Costas throw the restaurant’s garbage in the truck. The action takes about ten seconds, then, as quickly as the truck emerged, it drives down the road into the night.

They see the look of awe on my face. How did that happen? How did you know they were coming? “Crete Magic” they all say. Like many tourists, I come with a pre-packaged conception about Crete’s ancient supernaturalness. A waiter Tonya is nice enough to write down the Greek alphabet so I can at least pronounce the things I misconceive.

mmm… tourist products…

Do the old people on the post cards know that they are on post cards? How did the photographer find them? The thing that is similar between all of the faces is that they are wrinkled, tanned, missing teeth, and displaying a friendliness which makes you think that if you ran into them, they would take you into their old stone hovel and share with you their food and drink. Though they are poor, they are generous.

I walk over to a couple teens choosing postcards from the rack. They are going for more general scenic Crete ones, not the faces of the old people. 1 euro a postcard. Did the postcard subjects get any kickback? I think of the anonymous faces dispersed without consent or payment. Walker Evans’ portraits of Sharecroppers. Edward Curtis’ of Indigenous Americans. The horrific practice of lynching postcards. The lady in the postcard is somebody’s γιαγιά. Below each picture is written in script, Authentic Crete.

What does this term, authentic, mean in this context? Authentic in the Month of Mass Tourism means anything that survives in-spite of the world the tourists are coming from. Any practice that is resilient to the future the tourists return to.

mmm… sunset on the era of mass tourism…

Now the world we tourists came from has no form. It is too busy trying to decide what it is to impose itself on other places. This life in Crete for me is my life. It’s the only place I actually live. I’ll leave in a month, but I don’t know what world I’m “coming back to”. How can tourism exist when humans can’t go back home?

The answer lies in there being no back or forth, in time as a construct of capitalism, in possessive verbs in French in English, in America not being worthy of its creed, in Black Lives Mattering, in Indigenous language resurgence, in ending carbon dependence, in colors other than “red or blue”, in all the other stuff I wanted to write to you about. But instead, we’ll pause and shift to another story. Something about traditional music in Bretagne. It all started with a cabbage.

PART THREE

That Most Impervious of Qualities

Marthe Vassallo is one of those figures. Incomprehensibly cool and talented, she carries on the Breton signing tradition with what I identify as European cosmopolitan grace, mixed with an aura of bygone times. Her kind may have been standing on the cliffside, singing a long ballad for the return of a sailor. Not a sailor she loved but one she’d hexed with hydrangea petals and roses in the barnyard, with cidre and blood in the root cellar, or fire and metal at the lighthouse’s apogee. She was the emblem of the Bretange I’d imagined through the internet. Her presence on Youtube was as visceral to me as the moment I actually saw her, at the Saturday market in Vieux Marché, a small village in the Trégor region, where gangsters and cult leaders are said to be hiding out in estates far from the gaze of the world, and where activists for refugee rights in France are also the organizers of Fest Noz events.

I can hear Marthe’s voice even when she is silent and searching through winter vegetables. She reaches for a green cabbage a couple market stalls away from where I am standing, before a glass case of spiced chèvre. I have chosen a ball of cheese caked in turmeric, fennel seeds, and red pepper. As I pay, I turn my head to my coins, trying to decide wether or not to approach her. I turn my head back, and she has disappeared. All that is left of the woman I so dreamed of meeting was a vacancy in the pile of cabbages.

I was brought to this place by an important friend. Gabriel held the cheeses we’d purchased and I turned in the direction of his car. The smoke from chimneys laced the clear morning air. A church of sand colored stone rung 10:30 AM, ringing in yet another weekend of local life. I couldn’t tell Gabriel, a talented fiddler of many traditions, deeply engrained in the Breton music circuit, that I’d caught a glimpse of my hero, and was now wallowing in the tragedy of not having approached her. The words I might have said to Marthe floated in my brain. My regret billowed with the steam from villager’s cups of hot coffee. I cut my losses. Beyond the honey stand was Gabriel’s car, the Citroen which would carry me from the sting of missed opportunity.

“Where are you going?” He said as I walked toward the vehicle. “We have more business in this town.”

From base of my spine to nape of the my neck, I was filled with a sense of enchantment. The air was cold and I was still fragile, having spent the bulk of that month laid up in bed, suffering from the most severe flu that has ever befallen me. Perhaps it came from spending too long on the cliffside in the rain listening to the sound of distant bombard squealing in the harbor. Perhaps I’d caught my malady from the revelers at New Years festivities, from attending Fest Noz after Fest Noz, where the chains of country dancers held me close in rhythm, sweating into the night, warm with cider and the pleasure of company. The lack of food, lack of human contact, and the lack of physical movement endured from the couch had turned me into the kind of thing sensitive to invisible forces. I was the last leaf on a tree in the square, coming unstuck of its branch and floating now to the door of this ramshackle village house where our business was to be carried out.

We walked into this barn-like entry room, where antique furniture and farm equipment were situated in contrast to a stack of many fresh copies of the same magazine. Shoes and boots still warm from their wearers sat aligned next to another door. On the other side of it, I sensed the warmth of family life, peppered with another ingredient. I could taste it. The ephemeral thing which follows the kinds of people whose lives are made for art. There were people nearby whose work schedules do not align with regular business hours. There was a wooden table here in the entry, crooked with age and scarred by coats of paint. Upon it sat a green cabbage.

We entered a long stretch of living space, at the back of which was gathered a kind of council, circled around the woodstove. I passed through the air around me alert, as though every painting, every sculpture, every photograph hanging about the walls whispered yes, and urged me forward.

Her face is the same shape as the moon, yet carved to produce a jaw sharp with shadow. Her skin is like honey poured over parchment whereupon the first songs in the Breton language were scrawled. Around her were grown men paying rapturous attention to her words. They look up and greet us.

One is the owner of this home. He’s the director of a documentary about the Fest Noz, at the moment it became a piece of “immaterial patrimony”. This distinction is given by UNESCO, which keeps track of endangered languages like Breton. I sat by the director as Marthe was speaking. He and I said words to one another in hurried whispers. Each piece of language lingered in the air above the fire a moment and splashed upon him like a squall of rain, to which he responded by bursts of thought in turn. He did not have the vocal cadence of anyone I’d talked to before in this land. Artist! I had the feeling I was conspiring not so much with somebody but with something. There were chickens outside of the window in a courtyard. At one time this place was the home to a farming family. Now posters for the director’s films hang on the thick stone walls. Yet I could imagine him bent to the earth, humble, nurturing the soil outside, just as well as I could see him focused, taking in this world with a digital camera.

The place smelled of sweaters. Wet wool commingled with the steam of hot beverages and I was offered something to drink. In my hushed voice I said yes and introduced myself as writer, whose subject was the oral transmission of musique Bretonne itself. The weight of the room then shifted to envelop me. I was amidst and one of them, part of a covert operation. I’ll call it a resistance, but the threat is invisible. It is silence itself. We operate just under the surface, carrying the old way, through the tall grassed soaked with rain on a moon-drenched night.

The men are important. Along with the film director, I am introduced to the person who runs Dastum Media, which is the online archive of all Breton music recordings. The project started as a magazine at the critical juncture of the early 70s, when the last original speakers were approaching their deaths. Two my left were two professional and powerful instrumentalists. Across from me was a man from Poland, who ran a Breton music and dance association there, and was here to create a film featuring the interview he is now conducting with the queen of all of them.

She speaks in a way where I can imagine, that if elongated, her words would turn to song. She is calm and surrounded by that most impervious of qualities. Rapt attention from a group of men.

I have a hard time focusing on the words she speaks. We have shaken hands and have been formally introduced, but I am of not of the illusion we have connected or that she will remember me. This is not my goal. My goal is to be soaked by this environment. I want to remember everything. Her words crash over my ears as I sip the strong black tea. I rock in the wicker chair and notice a cat on the prowl. The window beyond Marthe’s head reveals the back of the church. We are all but meters away from the altar. I am aware that this has long been a sacred mound of land. Now the council has gathered to protect the thing with no true boundary. It is not God. It is music.

She speaks of a woman who gave her a hard time for having learned a version of a Breton gwerz from a 1990s field recording found on Dastum. She is then talking about a spring fed fountain. These stories go back and forth. She speaks, turning into the Polish man’s microphone. It is hard to catch every word. But she is talking about the limits of acceptable tradition in Breton music. I have already manufactured a belief, having seen her on Youtube, that she is the vanguard of what acceptable evolution of tradition is. Though the Breton music scene is dominated by male musicians, she shines brightest to me. She is neither pop star nor hometown hero. I’d put her age between 35 and 52, but her eyes scream childlike whimsy, and her comportment is that of a wise woman crone.

Marthe finishes a final talking point. The men start to murmur, and the circle is humming with the ideas of these people. I have a hard time accepting that this meeting should be adjourned. For I’ve arrived at the heart of my inquiry. I want to stay forever in the the unnamable core, in this world of tradition bearers, whose shared goal is to be of service to songs and melodies, which, I remind myself, are in French called airs. They are the stuff we breathe.

How will I elongate the morning so as to never make it end? I want to take a picture, or a covert video of the moment. Could I back up to the end of the room and take a shot of the group? No. Too corny. I opted instead to go the bathroom, leaving the company of all of them, and committing as much of the space to memory as possible. In the bathroom I looked over the chickens in strutting int he yard. The plucked away at the earth, scratching it with their talons, creating impressions.

There is something about that day I can’t hold onto no matter how hard I try.

I returned to the living room with desperation on my tongue. If I was smart I would ask her if I could call her and arrange an interview at her home. I should get the contact information for all of these people. By what means could I manufacture this feeling again? The sense of wonder and intrigue brought a lightness to my stomach, which was lately so twisted with flu and angst, because the constant search for comfort, as this comfort which now fades from me, drives me to want to consume the room. With a picture, I could at least prove that it once was like this. That I found the one I sought. She was putting on her coat. These people had places to be. She pulled her dark hair back and it poured over her shoulders like black water over river stones. I am not the customer, I am not the customer. I am the witness, I am the stranger, and I have heard the secrets of an ancient world, refracting through her vocal cords in this special time that she was alive, and I had the fortune of her company.

A badass from history - don't know the origins of this picture. But I found it on my computer right next to this one which was weird:

Melanie at a California Motel, 2014

OUTRO!

Before we part, here’s an announcement. I may or may not have an online birthday party wherein I show 0-3 music videos. I’ll keep ya in the loop. My birthday is August 30th.

Here are a few more recommendations too. Molly Young is a new friend made online who wrote this incredible thing about being in confinement, and has an awesome newsletter with book recommendations. Read the book White Tears by Hari Kunzru. I've been quoting it in the newsletter- it's about 78 collecting and white people stealing Black music. The miniseries on Netflix, Unorthodox, is really freaking good. There is this musical moment that brought me into a state of hysterically crying.

Selfie With Kitty - Chanià, Crete

E Kreiz an Noz, Volkslieder, dxʷləšucid, Wind as Original Speaker, Circle Pits, Glottal Stop, Local Television, Rock n' Roll School Teachers, and Jack Kerouac's Hotel

Sign up to receive newsletters here: http://tinyletter.com/westernfemale

Jack Keroauc’s Hotel from my window…

It brings me great pleasure to write you, as I have been so inspired lately, with an imagination full to bursting. This newsletter is going to be longer than the others have been, with many links, anecdotes, and ideas. So curl up with your cup of nog, or other festive beverage of choice, and come along for a ride into the depths of my mind on Bretagne.

This story starts with the first Breton song I fell in love with, called E Kreiz ah Noz by Youenn Gwernig. I encountered it while listening to a youtube mix of Breton music that might have been created by the algorithm. Youenn Gwernig was a poet who had to leave his Breton homeland for work in America. While living in The Bronx, he befriended Jack Kerouac and some other beatniks. Jack (Jacques) Kerouac and Gwernig made good friends, as Kerouac became more interested in his own Breton ancestry.

A gentleman in the bar below my apartment tells me that Jack Kerouac, when he came to Bretagne to discover his roots, inspired by his pal Youenn Gwernig no doubt, stayed in the hotel down the street. Apparently Kerouac was drunk and dejected for his entire stay on my road, la rue Victor Hugo, and had no success in finding the meaning he sought. I feel lucky to be enmeshed in the spaces named for and shared by dead poets.

I hope I can be a living poet though, and shed some light upon the also alive reality of Breton-ness. Breton is the language native to the place where I am in France, and bears no resemblance to French. Close linguistic relatives to Breton include Welsh, Cornish, and Gaelic Irish.

The language is considered ‘Endangered’ by UNESCO. Breton, like native North-American tongues, was forcefully forbade from being spoken in schools, and in public spaces, during the early half of the 20th century. These policies were a very effective way of taking Breton out of everyday life. I am a visitor to this part of the world in the decades following the Breton revival, which occurred hand-in-hand with the live amplification, and the recorded dissemination of Breton music during the 1960s and 70s.

A song is a welcoming thing, and thus it was the door I walked through when approaching the possibility of making the sounds of Breton myself. It is a language new to me as of this October. Each language is at its foundation musical, I believe, and each speaker of language is therefore a musician. If you don’t believe me, try speaking a sentence aloud, very slowly, while moving the tone of your voice up and down. Tell a story while doing this. This is how a song is created. Case closed.

So I hunkered down with the youtube video of E Kreiz an Noz, listened to it over and over again, used the slow-down feature to write down the lyrics phonetically, eventually committing the sounds as I heard them to my memory, until I was able to sing them back by heart, despite not really knowing what the words meant. Most Breton music, whether lyrical or instrumental is learned by ear, without tablature or written notation. E Kreiz an Noz, and Breton music in general, feels particularly accessible to me, as a person with very little formal musical training.

My life as a musician baffles me. My musicality “shouldn’t be”, according to the tenants of formal, western composition. And yet it is! As I reflect on my years making sounds wrongly, I realize how much of the music I know was learned by proximity to other musicians.

Just faking my way through Irish Trad Music Jam... Picture by Alexandre!

This summer, three high school friends and I visited a new exhibit at the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum in Washington State, where we grew up. Fearless Music “explores four decades (1980 - 2018) of a vibrant, independent music scene on Bainbridge Island”. The exhibit featured interviews and artifacts literally collected from the people I visited the exhibit with. A recording of Charlie talking about The Blood Barn played back from a speaker on the wall. A flyer with John’s face on it hung amongst others preserved from shows at the Bainbridge Grange. The ephemera of the music we made and danced to as teenagers stared back at us. As we walked out of the museum, one of us vocalized what we were all feeling. “Well, we’re history now”.

Was the museum wrong in creating boundaries around a time, and a movement? Was the existence of the exhibit itself the final death blow to it? Those who had created the exhibit had found that punk and DIY scene on our island had existed as a forty-year continuum. Now there was little to no sign of it occurring. This fact is corroborated by my younger siblings, who did not spend their weekends thrashing in moshpits, nor have the multifarious options to do so as I did. Commemorating the music now made sense.

The droning heavy metal, the circle pits, and the handmade fliers that accompanied performances which to me bordered on ritual, had fallen asleep, decomposed, gone back to the island whose boundaries created the conditions for a homemade creativity, as we were compelled to invent our own entertainment.

I watch videos of Bainbridge Island musicians from this period of "Fearless Music", online. The first takes place in 1983 or 84, and features frontman of Malfunksun, Andrew Wood, pandering to his audience. I write down what he says, as it seems to me a manifesto for the forty years that followed him: “We’re here. We’re not just going to let it go on like a little show. We want to see the whole place going wild like these smart people over here. Now you people, you’re wasting the floor! Go sit at the bar if you’re gonna do that. I want you to all sweat.”

His message is clear. Either you participate, or you get out of the way. Malfunkshun’s proto-grunge drone begins, and the people start to writhe. Another video exists from 1992, of a band called The Rickets playing at Island Center Hall on Bainbridge. The camera focuses less on the musicians and more on the audience, who appear between flashes of strobe, flailing their limbs in all directions as they run around in a circle, knocking into one another, bouncing off one another, becoming an extension of the music, which sounds a lot like the Malfunkshun song played ten years earlier.

From 2006-9, when I was in high school, I spent my Friday nights in that very same hall, making the very same motions, albeit in a smaller and more dense circular nebula of bodies, to bands that basically sounded the same as Malfunkshun or The Rickets. I didn’t know why we did what we were doing. Only now do I realize that these nights were manifestations of oral tradition, were intergenerational imitations, were expressions that adhere to the very definition of a regional music and dance.

Typical Herder.

Maybe more specifically, to the first category of what a folk-music is, according to the person who invented the concept of folk-song in the first place. Johann Gottfried von Herder, a German philosopher and student of Emmanuel Kant, coins the term “folksong” with his 1778 classic, Volkslieder. The “most pure” version of folksongs, are “songs transmitted from generation to generation by the oral voice, amplified in the mouths of peasants, fishermen, etc.” (translation mine)

We teen folk of Bainbridge Isle, in the period from 1980-2018, were this “etc”.

The band I danced to then, WEEED, continues to play together now, and toured in Europe this (r)oc(k)tober. Afterwards, drummer Evan and his partner Claire came to visit me in Brest. We went to a small Fest Noz together. A Fest Noz is an event of Breton music and dance that takes place at night, and a Fest Deiz is the same thing, but in the day. Musicians play and/or sing Breton pieces, and a circle of people dance arm-in-arm, in coordination. This continues for hours.

At the Fest Noz, I watch as Evan records some of the music as a voice-memo on his phone. “This sounds exactly like a WEEED riff,” he says of the Breton melody.

Rolling around with Evan and Claire at Ateliers Capucins

Interesting.

When I arrived at my first Fest Noz this September, I had the distinct feeling I’d been at something similar to it, before. The circle of bodies, the droning modal music, the cheap entry fee- it all felt so familiar somehow. As I walked into the mist down by the beach to reflect, I understood how the DIY musical renaissance in Bretange was, not only analogous to the homemade hardcore shows of my youth, the “fearless music” of my home island, but to square dances and honky tonk dances I have been playing and participating in for the last ten years of my life.

The Breton Beach of Pays Pagan

I look up another video online. It’s a clip of my friend and bandmate Joanne Pontrello calling a square dance in the Tractor Tavern in Ballard, Washington while the Tallboys String-Band plays in 2011. The band only exists because the people dance. The people dance only because the band exists. Circles form, strings moan. Joanne directs.

Call this youtube spiral of mine extreme home-sickness, but it is also something else. Through the internet, I see myriad expressions of the regional creativity of the place I am from, and appreciate what I know and do not know about it. The Tallboys used to play at The Pike Place Market. I heard a reflection recently from writer Sean Jewell, that anyone who busks at the Pike Place Market long enough, develops a kind of grating voice as a device to cut through the sounds of crowds, fishmongers, and the downtown drone of vehicles. This vocal quality is evidenced clearly in a video of Baby Gramps from 1984. I am told that I too have developed this vocal quality, which is basically just abrasive projection. I am sure this comes from having had to scream at the market while playing music.

With Davey Haul at Pike Place Market in 2016 I think. Picture by Heather Littlefield!

In the most mystical manifestation of a Christmas Miracle I could ever dream of, fish monger and proprietor of Jack’s Fish Spot in the Pike Place Market, Jack Mathers, has created this Christmas music video, “The Brand New Christmas”, which is filmed at the market, and features a wide variety of characters who hang around and work there. Jack has been the employer of least two generations of my family members, the Currans, so witnessing his creative output hits extremely close to home.

My mom wrote in our family text chain about Jack’s music video, “Now if that doesn’t get you in the Northwest Christmas spirit, u r NOT from the NW!” True. My sister wrote, “That’s the most Seattle thing I have ever seen. He even managed to make it 4:20 minutes long.” Which is remarkable, because the song itself only lasts 3 minutes and 40 seconds. My father writes one thing only: “Yes this is real”.

Although my father’s comment may seem redundant, the reality of the video’s reality, is something worthy of pointed focus. The Brand New Christmas is evidence that on December 19th, 2019, a regional, brand new, old school, low-budget, living folkloric creative entity thrived into digital existence, and defies the categorization of what traditional music even is.

When Herder decides in the late 1700s, who the real “Folk” are, he also does the initial work of removing the idea of these artists from the academy, the city, and the state progressing toward modernity. Herder was a romantic, in that he was a leading force of the romantic movement, which cast the “backwards country people” under a blanket of nostalgia.

Viewed from a place of remove by the experts, the “people” and their art forms always seem on the verge of disappearing. The authentic and pure forms of humanity, unsploit by modernity, are described in word that turns what is occurring right now, into already being history. Songs, poems, and stories are therefore relics, artifacts, excavated gems. In 1918, Breton music was described by a French intellectual Charles Quef, who came to the region to analyze Breton music:

“It is the Breton tenacity (proverbial in France) which has been able to preserve their precious and ancient artistic heritage almost intact and with many traces of its primitive origin. We must rejoice over this, for we are enabled by that tenacity (we might almost say stubbornness) to possess a jewel wherein we can admire one of the finest and most peculiar branches of the popular musical art of France.”

For hundreds of years now, the modern, advanced, knowing world has been making relics of very real, existing, arts of those tenacious enough to "preserve their precious and ancient artistic heritage."

Charles Quef, were you jealous? Were you unable to see yourself as other to something unknowable to you? Did it cross your mind that that jewel you possessed (Bretagne) might have had as much intellectual and creative power as anything you’d been touched by in your life? Did it hurt you to have this line of demarcation etched in your brain and heart? To believe so hard in the division, between the traditional, and its opposite, the now-happening?

I personally like to mess with “the traditional”, in terms of old-time music. Consider this term! Old Time. What time is that? When did it become old? This month I created a Youtube banjo video with my updated version of Fred Cockerham’s clawhammer hit from I think 1939, Roustabout, which is a tune that goes back even further in African American banjo music, first recorded by Dink Roberts, and Josh Thomas. I call my song Roustabout for the Modern Woman. In the same vein, I made a song/video a few years ago called Shady Grove for The Modern Woman.

I create these updated old-time songs mostly to entertain myself, but they function as resistance to the notion that a folksong lives in an imagined, and more authentic past.

Bretagne (Breizh) especially bears the brunt of being shrouded in a past tense by the outside world, that de-authenticates its current expressions. But they are alive! I will give you an example from a couple nights ago.

I am standing outside of a bar in Brest, talking to a couple guys in the rain. I ask them my usual questions. Are you musicians? Do you speak Breton? One of the guys says yes to both. Feeling particularly fearless (this moment brought to you by Correff Bio), I say that I know only one song in Breton. I proceed to sing E Kreiz ah Noz, the way I have learned it off of Youtube.

To my joy, he starts starts singing with me. I purposely slow my singing down, just a touch, so that I can echo his pronunciations. I self-correct in correlation with him, and learn a different way of making the sounds I thought I knew, kind of.

By having a living, breathing person in front of me, agreeing on the sounds in real time, making music in coordination, I sense the Breton language as not so endangered, but as manifesting in ways not yet considered active.

This person goes on to tell me that he himself has written a song in Breton, recently. It is about the first time a Jazz band to ever came to Europe. The band arrived by boat, here, in the harbor of Brest, he tells me, describing the arrival of a black band from America. He starts to sing his song. I recognize few words. “Jazz Afro-Americain”, and Brest, and a refrain of our/my Brest.

A song emerges that defies what an elderly archivist told me a couple months ago. If you are here to collect songs Melanie Curran, you don’t need to. All Breton folksongs have already been collected.

This is a traditionalist’s definition of tradition. I long for a more absurd definition or conceptual frame.

Ahem, for example:

The ideal field recording to me, is the one I made of the only Breton song I know, E Kreiz an Noz, being screamed by young drunk men on a shuttle bus at 6 in the morning, heading back to downtown Rennes.

In this field recording, captured on November 24th, 2019, one hears the lyrics of Bretagne’s Bob Dylan, Youenn Gwernig’s E Kreiz an Noz, being “butchered” by a very loud and passionate male. Others on the bus attempt to sing with him, while forgetting the lyrics. Other voices are heard speaking French, as the bus prepares to drop off its passengers from the night they have shared in an airplane hanger on the outskirts of the city. They were at The Largest Fest-Noz in Bretagne, Yaouank, which in Breton means “Youth”. Bretagne’s local television channel, France 3 Bretagne, created a 2 minute and 43 second spot on the event, and described it as having been “12 Hours of Dance”.

Such a huge event.

At minute 1:10 in this video, a young male-appearing person in a tank top emerges on the screen. He is, in fact, someone I danced a waltz with that night. Of the Yaouank experience, he expresses the following sentiment for the news camera (translation mine): "I have the impression that life often lacks a social connection. And the fact that it is found here, with so many people, linked arm-in-arm- makes me see how it is missing the rest of the time. It reconnects our hearts, and it reconnects us to others.”

Scene.

Through channel France 3 Bretagne, Bretagne can see itself reflected as existing, although through a kind-of removed journalistic tone. The tone is like - wow! We can’t even believe all of these things are happening, right here in Bretagne! Even though we live here! There have been multiple times in the last couple months when I’ve met someone, googled their name or organization, and found videos about them and their work by Bretagne 3. The station’s headquarters is located a few minutes walk from my house. But this local TV station’s power to represent the people of this land, pales in comparison to what is probably the most amazing homemade social networking website in the world, www.tamm-kreiz.bzh.

This website exists for one reason and one reason only. To tell people where the Festoù-Noz and Deiz are, and when they are happening. It is also a way to see who is playing at them. You can click on the name of a group and find out which musicians are in it. Then you can click on the name of the musician and see what other bands they are in. You can see when those bands are playing and where. You can see who is attending the event. There is a rideshare message board. Tamm-Kreiz gives me hope that there can be alternate social medias, people’s-facebooks, sites that actually foster human relationship in real time, at real events, instead of propagating isolation and anxiety as many report instagram does.

On Tamm-Kreiz, I have accidentally stumbled upon the profiles of people I’ve met in person. The website shows me what incredible, prolific musicians they are. One of these people is the highly badass Sterenn, who plays in many groups, one of which is this fabulous all-female trio called Dixit.

The evening of Yaouank, I meet Sterenn for the first time and get to stay at the house of her and her roommate in Rennes. I have been put into connection with the two of them through a musician named Gab in Brest, who I, of course, met at a bar. I promise I am not spending this entire Fulbright period in bars. They are absolutely a part of my ethnographic strategy, though.

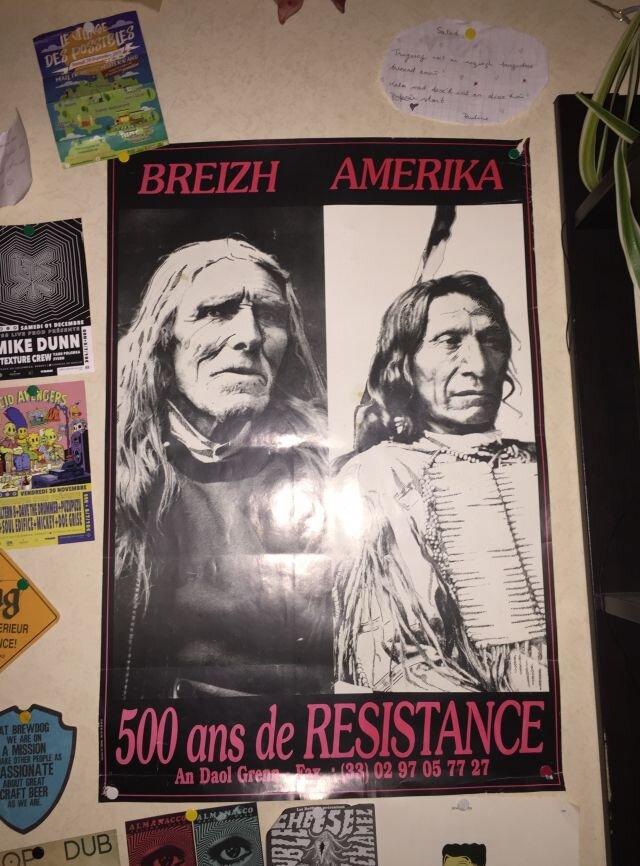

Sterenn’s apartment is sort of like the Fearless Music exhibit, in that the walls are covered in flyers from Festou-Noz/Deiz she has attended, or played at, or both. Also on the wall is the of an elderly Breton man side by side with a Native-American. Which reads, Bretagne / America, 500 years of Resistance.

A vintage poster in a Rennes living room

What is different about this space, is that it is not a museum, but a place in the act of resisting. It is a smoke-filled, people-filled living-room where people in their early 20s are harmonizing together, singing what sound to me like ancient medieval ballads in many part harmony.

They do this between plays of songs on Youtube, such as Super Freak and Crocodile Rock, and other more modern songs I don’t know the names of, because I have a tendency to only notice things from the 70s. Eventually they ask me what kind of Breton music I have started to listen to.

Thank God for you, Youenn Gwernig. I put on E Kreiz an Noz, the only song I can remember, which I can barely spell at this point. I find the song on youtube mostly because I recognize the picture of Youenn, standing stoically in a field, and looking off into the windy horizon, hands in pockets.

The song plays, and every person in that room sings along. It’s beautiful to me. These young people are admittedly all Breton musicians, but for a moment I want to believe that all young people in Bretagne sing old songs together on Saturday nights. I understand that some of the people at this party knew each other from having been classmates in the Diwan, or bi-lingual Breton school system.

The system of bi-lingual Breton schools is referred to by France 3 Bretagne as this struggling, archaic entity. There is a hard-hitting news story called, What Future for the Diwan Schools? The more I learn about Diwan, the more I am impressed by the way they have resisted being un-futured by the outside world, and apparently their own local news network.

How Diwan was made is a legend of rock n' roll and passion. In 1977, a child in Bretagne was hard-pressed to find an elder who could speak to them in the native tongue. So effective was the process of language repression, that most primary speakers had been silenced.

With the Breton musical revival in the 70s, came the recording of songs and oral histories, which resulted in a boundless creativity, as younger musicians riffed off what came before them, now accessible at the newly invented Festoú Noz and Deiz, or through records.

Young musicians entwined new genre influences in their song-writing, while remaining in fidelity to lyrics and rhythmic structures of Breton sound. The most well-known pioneers of the revival, is Alan Stivell, whose 1971 album Renaissance of The Celtic Harp, is a cornerstone of Breton recorded sound from that period.

It is the band Storlok though, which is given the title of the first Breton Rock Band. The leader of this band, Denez Abernot, is described on wikipedia as a auteur-composer-interpreter, a fisherman and boat captain, and an actor. He was also the first teacher of the first Diwan class in 1977, which consisted of five children. The height of his rock n’ roll career and his teaching career occurred simultaneously.

This gives me hope. That a local rockstar/fisherman can start teaching kids the language of their elders, at a homemade school. Diwan started with five kids and a singer. Now there are 4,337 students in attendance at 54 Diwan schools in Bretagne.

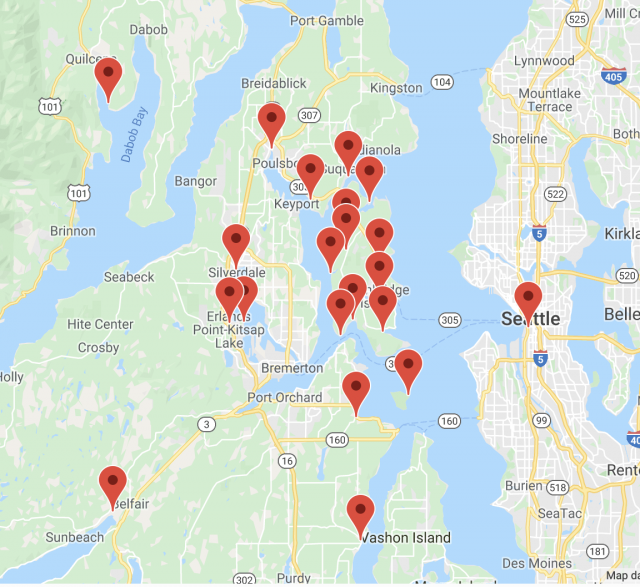

Writing about and from this place, I see the Puget Sound in glimpses of memory. For the first time in my life, I look up the Suquamish Tribe’s website. These are the people whose land my ancestors homesteaded on Bainbridge Island, and whose land my family still occupies.

As I look at the map on the Tribe’s website, I see that many of the beaches I grew up on are the sites of permanent winter settlements, long-houses, and places where Tribal life articulates in the dxʷləšucid / Twulshootseed. Albeit no longer with those structures in place. Those beaches look like waterfront property and no-trespassing signs and road ends and parking lots and kayaks stacked up.

Locations of Suquamish Winter Settlements

I switch to present tense here on purpose, as a way of suggesting that the indigenous language of the Puget Sound, described often as coming literally from the land, is still there. That a white/anglo linguistic reality has been superimposed over this space, and it doesn’t completely fit. English lacks the capacity to describe and make real the Puget Sound environment, and the American environment, even to colonizer-Americans, who seem to be ever-longing for their roots.

Take Jack Kerouac, in his hotel room, drunk, finding nothing of himself in Bretagne. Listening to the same tones of wind, pulsing as they do now, down the rue Victor Hugo.

I also notice on the map that the sites of settlements of the Suquamish on Bainbridge, are now public beaches. Places that I went often alone growing up. Places I return to when I am back home now. I got to these places because I find it easy to do a few things while at them: To play music, to write poetry, and to clear my head, by listening. Tom Waits says “A song is just something interesting to do with the air.” I think the air on those beaches is the kind of air that wants to be made interesting.

The map points to the location of one such settlement in what is now called Eagle Harbor, where the Bainbridge / Seattle ferry comes. A memory comes to me. I walked down to that beach once, and put a stone in my mouth. I sucked on it, desiring for the stone to tell me something about the way my mother had lived on the island, the way my grandparents had lived on the island, and back and back. I did it simply because I felt like I didn’t know enough about the place I grew up. I wasn’t stoned or anything, I just had the literal feeling that I could access a new sense of how to understand, by putting the rock in my mouth. Sort of like learning a new word.

I enter cautiously into my research of Salish languages. As I do in Bretagne, I feel like I am a visitor to these websites. What I want to know is how language revival looks for the tribes whose land I grew up on. I am aware that I have never made an effort to consider this before. Bretagne points me toward the investigation of the place I am from, and the language that is indigenous to that place.

I learn many things online.

I learn that the indigenous language of the Salish people is alive, evolving, and being taught. The Puyallup Language Program is a very active group of people working for the language. Their mission statement is straightforward: "Our goal is to revitalize the Twulshootseed Language. The method we find most effective is to just speak the language."

One of the practices for described for implementing dxʷləšucid into daily life is to create “a language nest”, or a designated place in the house where only dxʷləšucid is be spoken. In this way, learning a language, and making it part of your life, becomes an act of performance art, according to Zalmai Zahir, who “may be the most fluent dxʷləšucid speaker now alive”.

Concurrent with state-sanctioned efforts to mute Breton language in school and public places, was a similar, but more violent effort to do the same in America with indigenous tongues. To reverse this, the making-daily of language has to be somewhat forced. Institutions like the Diwan schools in Bretagne are an example of how designating a space for a language to live, is how a place can teach a language back to its listeners.

I suggest that grunge, droning rock n’ roll in Kitsap county community halls, circle-pits, square dances, vocalizations of Pike Place buskers, are a version of authentic oral patrimony of the Pacific Northwest. That these music forms are repetitions and reactions and impressions of sounds made by ferries docking, rigging hitting metal, trees shaking, rain falling, sewer grates clogging with pine needles, the gathering of sap underneath bark, the collapse and crunch of the cement and rebar of the viaduct being torn-down.

As I watch instructional Youtube videos about the dxʷləšucid / Twulshootseed language, I think of how generations of my Bainbridge Island family have both been deaf to, and have accidentally heard this language over more than a century.

In Port Madison bay, dxʷləšucid is not lost, or dead, but rather is in the process of being concealed by a history of real estate proceedings, architectural marvels, overfishing, yachts. My family, the Johnsens, possess a text of dock, bulkhead, basement, hot tub, elevated porch, and living room, where in a few days my family will spend Christmas together. There is a language of Nat King Cole, and a language of gift paper unwrapping. How can activity of my family’s settlement at the head of the bay be interpreted as music, and a music which allows for the vocalization of dxʷləšucid?

The other night I went to sleep asking my Puget Sound ancestors, both related to me by blood and not, to let me know what I needed to understand to be a writer, artist-musician, and active-ator-ist of “the traditional”.

In my dream I was on a windy outcropping by the raging sea, in the rain, in Bretagne. It could have been a Puget Sound place too. There were many large tents designated for music making. I had to help take them down so that they wind wouldn’t blow them away. As I did this, I saw another, smaller tent, made for camping. There was blood pooling out of the back of it, where a head might be laying inside. I said to aloud, What is that, the death of a language?

I woke up to the sense that my room was full of people, who were all making the glottal stop in unison, a sound I’d practiced that night when repeating the sounds of the dxʷləšucid alphabet, from an online video.

I opened my eyes and looked around for these people, but my room was dark and empty. Outside the wind howled through Brest. The way a dream leaves you with an idea you are absolutely sure of. For example I knew then that wind taught people to create both language and song. That the hitting of something rhythmically on my window was a potential origin of the glottal stop.

To hear dxʷləšucid, I listen to the storytelling of Vi Hilbert, watch videos made by the Puyallup Tribal Language Program, and watch Zalmai Zahir narrate the process of frying an egg. I listen to an episode of the All My Relations Podcast on the importance of activating native language use in North America, where I learn that a person who is able to tell their creation story in their tribal language, is much less likely to commit suicide than someone who can't.

Words are the foundations of poems and lyrics, through and with them, meaning, time, and physical space, act.

I hope that by sharing the Breton world I witness, I can use language to make verbal, to make into verbs, the words that stand-still, like nouns! Folk (ing) Volks (ing) People (ing).

By preferring verbs, can I use language to help in the decolonizing of regions affected by the destructive migration of people who have had the same skin color, facial structures, light eyes, as me?

As a white person, as an English listener/speaker, as a scholar, as a writer, can I accept what I do not understand, without imposing English on what I witness? Can I listen to Chet Baker’s Almost Blue and not hear the words as words but only as raw sound? I almost do this in my living room one night, and it's sort of like when you repeat a word over and over until you forget what it means.

If you are not bi-lingual or poly-lingual, I can only encourage you to let yourself enter the space of not understanding a language, of being confused by it, willingly. Knowing not knowing as an alternate wisdom.

There is enough that has already by agreed upon and rationalized.

The internet provides many opportunities to get lost. I impose confusion on myself by listening to a Breton language radio station for a day. Or to the Sicilian songs sung by Matilde Politi. To music made by the Ainu people of Japan. I have no idea what the words mean, and yet, I have ideas about what they might imply, which I let pass through me like small tempests.

There is still so much I don’t know about in Breton life, and probably never will. I take account of the things I witness, I put them down in an order according to the way my brain makes meaning of experiences.

The most intricate dance in Bretagne is called The Fisel. I watch a video of a Fisel competition. Even though this is a public event, and individuals are scored, I notice how the dance relies on being passed around the circle, from person to person. One cannot do it alone.

I meet a person in a bar who is young and organizes the Festival Fisel. He is wearing a baseball cap that says Folklore, and says Folklore is like his sports team, because he doesn’t play like soccer or baseball. This hat is created by a French Canadian musician with incredible red hair whom I have met at Fiddle Tunes.

I play Irish music with my friend in Brest, who has learned tenor banjo through youtube videos. He makes a recording of me singing John Prine’s Paradise, and saying phrases about saving the environment. He puts these recordings of me to electronic beats in his apartment. This is regional music in Brest in the sense it is music created in Brest.

Yann Tiersen, the composer of the soundtrack for 2002’s Amélie, is from also from Brest (Brestois) and recently performed at a free concert for Diwan Schools, which I attended. I noticed how his compositions, particularly one for the violin, rely on what I understand as a drone in modal music. He recently released an album which was recorded on the most Northwestern island in Europe, Bretagne’s Ouessant, where he now lives.

The droning violin song is call Introductory Movement. I find it on Youtube. The recording features the use of heavy guitar, played by Stephen O’Malley, one half of drone-metal band Sunn O))). O’Malley and his band hail from Seattle, Washington.

The weather here is familiar to me, in the sense it is like Seattle’s. Rain and Grey skies abound. I hear the calls of seagulls in the morning. What I am not used to though, is the wind.

The wind sweeps away weather like a sponge over a counter-top. The wind comes from all directions at once, and transforms the day I thought I was having in the morning, to a completely different kind of day by afternoon. I am still. The lyrics of E Kreiz an Noz, speak of the phenomenon of these winds, blowing through a concentrated center. E Kreiz an Noz means, In the Middle of the Night.

“It’s weird that you like this song,” said one of the musicians in Sterenn’s living room, the night of Yauoank. “No, like, it’s weird because of the fact you’re American.”

I’m still trying to figure out what was meant by this.

I get a Breton/French dictionary from the library.

The song’s first four verses talk about four winds. A wind from the East- a metaphor for the influence coming from Paris, or the centralized French government which suppresses Breton language / culture, I think. A wind from the West, or America, where Gwernig immigrates to find employment, and also meets Jack Kerouac. Jack Kerouac, the saint of wanderers, Sûr la Route, On the Road. A third wind that comes from the sea, and a fourth wind that comes from the earth itself.

Each of these winds arrive in the middle of the night, and blow over the place where Youenn, or any Breton person, lives. House as is Chez as in Pays as in home-country as in father-land. The fifth and final verse says, It doesn’t matter from which direction the winds come, because every kind of wind carries both the desire to live with, and the potential of having already acquired, liberty in Bretagne.

The noun Kreiz, middle/center, sounds like the verb that follows it in the chorus, c’hwezit, meaning blowing.

The still middle can resemble an active blowing. A woman in a bar (yes another bar) asks me if I have ever stood in the middle of the bridge Recouvrance, which spans the Penfeld River dividing Brest in half, during a windstorm.

“The other night,” she says, “I stood at the midpoint of the bridge while the wind was blowing furiously. And I tell you, the bridge was singing.”

Wind as song maker, wind as storyteller. Wind as original musician playing the material of the earth.

I take the Breton word for “wind”, avel, and put it into Dastum’s search engine. Dastum is another miraculous Breton website, where the entire recorded archives of Breton music, called the “oral patrimony”, are available online. Following the word avel, I listen to a snippet of an old woman singing, a conversation in Breton, and a beautiful melody.

A singer in town tells me she uses the Dastum resource often to learn new songs, which she then teaches her students, by ear, by call and response. Word of mouth, literally mouth to ear, or bouche à l’orielle.

Are we not better equipped to be singing, living, and creating new traditional music today, having the company of so many ghosts?

These traces of musicians, remaining through recordings, are not limited to Bretagne. The American website, slippery-hill, has a similar archive of field recordings of fiddle tunes. Including very recently made “field recordings”.

Barba Loutig in the Vauban Basement

The most beautiful Breton band I have seen so far is called Barba Loutig. This is a four person, all-female band that employs voice and percussion only. Theirs was one of the the most powerful live performances I have ever seen. I was crying a lot. My emotions had something to do with the way they took Breton music, and wove other sounds from around the world.

I go to a conference on the digitization of traditional music, and the opening sentiment is from a man who says that traditional music is not here to amuse. It is instead a river that is growing, that is gathering more force. He uses the active verbs.

Someone else on the panel says Breton music has a habitude de mélanger, a habit of mixing. I watch the Barba Loutig that evening, at a musical festival in Brest called “No Border”, which is how their music sounds.